Recently discovered picture (2022) showing what can only be me as a baby with mum’s older brother Uncle Tom and a young Uncle Danny and Aunty Hazel. Taken in the front garden at 224 Riddings Road.

224 Riddings Road

1947-1958

Riddings Road is the main street of the large social housing estate, built by Huddersfield Council in the working-class area of Deighton in the late 1930s. My grandparents James Owen Leonard & Laura Leonard were listed as the occupants of number 224 in the 1939 Census, together with their four children, which included my mother Catherine Margaret Leonard. The family was later to increase to six offspring.

My grandparents were most likely the first tenants of this rented property, which – with gardens front and rear and an inside toilet/bathroom – must have been a dream move for them, as previously they had inhabited a terraced house in the congested slum area of Castlegate below Huddersfield town centre. (Victorian era Castlegate was demolished as soon as residents had been successfully moved out to one of the many new council estates being built around the town).

"Laykin' Alliz"

Some people have amazing memories, capable of recalling events from earliest childhood. I am not one of these. For some reason – and certainly out of the time cycle – my first clear recollection from around the age of four is that of playing marbles with young friends on the grassed bank just down the road from my house.

Or “laykin’ alliz”

as we called it in our local Yorkshire dialect.

Later education was to show that use of the word “layk”

to mean “play”

was not lazy English - of which we were often accused at the time - but one of the few examples of our one thousand years old Viking heritage still evident in local language. The same word root is found in the Danish product LEGO, which is an abbreviation of "leg godt", meaning “play well”.

But why were marbles called “alliz”? Until very recently I really had no idea. Then a contact gave me the logical explanation that, as the original play marbles were made of alabaster, they first received this abbreviated pet name. This just goes to show that you are never too old to learn something new.

In the early 1950s, we kids were generally left to our own devices for amusement, usually outdoors. Friends would call at the door and ask “Is yer Leo laykin’ art?”

(I was known as “Leo” all my childhood, much to my mother’s annoyance).

This was a time without TV and the streets were devoid of traffic and dangers, imagined or otherwise. It was not unusual for my mother at teatime to stand at the door and shout “Brian!”, when my friends would let me know “Leo, yer mum wants yer”. This really was an uncomplicated age.

Without the influences of mass entertainment, other than the local cinema, it was remarkable how the games we played were naturally seasonal. Every spring, around Easter, would become the time for marbles for boys and whips & tops for girls. Bags of coloured glass marbles would appear overnight in the shops, along with the whips & tops. (The spinning tops were egg cup shaped wooden pieces with a metal covered point and flat top. The whips were used to start and continue the top’s rotation).

Accessories available at the same time were boxes of coloured chalk, used both to decorate the crown of the spinning top, as well as for marking out hopscotch areas. When you saw chalk packs on sale, you knew summer was on the way. And I still remember the joy of returning home with a bulging pocket of marbles in my short trousers, having hit a winning streak…

My Grandfather's Death

Visits Away from Home

I only took one holiday in my childhood. As I do not recall my grandfather being with us, I have a feeling that this happened soon after his death, possibly as a recuperative break for my mother, my uncle Danny, my auntie Hazel and me. We chose to go to Rhyl in North Wales, at that time a very popular traditional seaside resort. I think that we spent only a couple of days there, but it certainly made an impression on me.

I recall the wonder of sleeping alone in a bed with a quilted cover for the first time. At home I shared a bed with my uncle, where we had a single woollen blanket covering, which had to be supplemented with overcoats on colder nights.

The room at our bed and breakfast hotel in Rhyl also had something I’d never seen before – a filled jug and bowl set for washing. I can still visualise their blue pattern and recall the overwhelming smell of lavender in the room.

New Clothes at Whitsuntide

Ask anyone locally from the 'baby boomer' generation (i.e. those born within a few years of the end of World War 2) what Whitsuntide means to them and they will invariably answer “new clothes”.

I regret that I cannot offer a definitive explanation why this – now generally ignored – religious festival should have been associated in my childhood with youngsters dressing in best attire. Certainly, the practice died out with my generation; I do not recall any pressure to buy new clothing for my children on the seventh Sunday after Easter.

Deighton County Primary School

If my calculations are correct, I started full-time school just two days before my fifth birthday.

Due to the rulings of the time, even those approaching five were admitted at the beginning of the school year. The cut-off date for acceptance was something like mid-September, making me one of the youngest in the class throughout the whole of my education. Many educationalists have argued the unfairness of putting starter groups together where some were nearly one year ahead of fellow pupils in terms of physical and mental development. However, apart from the fact that I was generally smaller than my classmates – even the girls – any age-related disadvantage was never noticed by me.

In those days there was no such thing as pre-school preparation. Unless you went to a private establishment, that is. And Deighton simply wasn’t that the kind of area where paid-for education was even the remotest option. Children there were just transported from the playing field to the classroom at one fell swoop.

Having been taught – and encouraged – to read by my mother and grandfather at home prior to starting school, I was immediately assessed as being in the top class. I never shone, quickly realising how to do just enough to satisfy others without overtaxing myself. I wasn’t lazy; I simply don’t remember being particularly inspired by the teaching staff. I was happy to quietly go along with the flow, preferring not to stand out positively or negatively.

Probably reflecting the working class, relatively poor status of the neighbourhood, the school did not have a rigorously enforced uniform policy. Boys were expected to wear white shirts and short trousers, girls white blouses and skirts. Some were dressed better than others, although overall no-one paid that much attention to smartness, accepting that money for school clothing was limited everywhere. I can recall how my mother was almost reduced to tears when I returned home from school with torn shorts or – even worse – with worn-through shoes. Times were hard, but everyone was in the same boat.

Organised school clothing exchanges were still generations away but I am convinced that, even if they were around then, engrained parental pride would have limited their uptake.

One awkward fact from my childhood: I did not wear underpants until in my late teens. Naturally, I saw other boys wearing underclothing when changing for games, etc., but to my mind this was just a sign that they came from better-off families. I never considered it to be strange that I did not mirror their routine. After all, there were other boys who – like me – habitually 'went commando'.

Another interesting factor in reflection of the times: the school was made up one hundred percent of white pupils and teaching staff. In Deighton there was a concentration of second-generation Irish, particularly around Riddings Road. There were also children of Italian, Polish and Ukrainian fathers, who had come to the area originally as soldiers or prisoners of war, before marrying local girls and deciding to stay. The first waves of invited West Indian and Asian mass immigration, who were to settle later in this district, were still a few years away.

Notwithstanding my typically casual approach to learning, I was capable of putting extra effort in when required. Even at the age of ten I was aware that, were I to pass the 11+ Examination, this would make my mother proud. It would also be one in the eye for those who had been freely critical of her performance as a single mother.

The 11+ Examination was the much disputed, later abandoned, system of identifying and isolating early those pupils who would apparently benefit from a higher standard of secondary education (i.e. in grammar schools). I know that, at the time, I professed that I wanted to go on to the local secondary modern school with the rest of my friends, but deep down this was never an option. It would be a pass for my mum.

In the event, the exam – taken on a Saturday morning by the whole year in the school’s main hall – was somewhat unexpectedly no major problem for me. In retrospect, it was similar to the IQ tests at which I was to later excel. I must have done well here too, because when my results were filtered into the area’s system, they placed me into the second ('A') class out of the five in the first year at grammar school.

Deighton – a relatively new school in a deprived area of the town – was not expected to offer up many candidates to the grammar school system. It transpired that the school exceeded all forecasts, a fact which I recollect utterly delighted our headmaster in his parting address to us.

Having received my positive result, my mother and I were given the options for local grammar schools to attend: King James’s Grammar School – a historical stone-built edifice in Almondbury; St Augustine’s – a new Catholic grammar school in Bradley; Huddersfield New College – an amalgamation of two old establishments, Huddersfield College and Hillhouse Technical School, on a new-build site at Salendine Nook. All would require taking two bus rides, so distance was not a factor. Only St Augustine’s was mixed; the others were for boys only.

For no other reason that I fancied the newer school, my mother let me choose Huddersfield New College.

The consequences of my decision were to act themselves out quickly. Within a few days of making my selection, there was a loud knocking on our door. The infamous Father Power, the feared local Catholic priest, had arrived on his motorbike, demanding to know why I had not chosen St Augustine’s. To my mother’s credit, she backed my decision to the hilt, leaving the priest to depart in a rant, shouting words in his broad Irish brogue to the effect of “You’ll burn in Hell!”.

Rex and Other Influences

My mother got me a dog for my sixth birthday. A large brown and white cross-collie, he was the best pal a lad could have. This was to lead to my lifelong love of dogs, a trait I am pleased to say was passed on to my children and grandchildren.

Given the then popular name of 'Rex' – Latin for 'King' – he was my constant companion. He led a life that would be hard for people to accept nowadays. He was seldom on a lead, just left to wander in and out of the house as he wished. (The house was only locked up at night, with the doors often left wide open when the weather permitted).

It shames me now to say that I never thought to routinely clear up his mess; after all, neither did other owners. He stayed close to the house and almost invariably answered calls to come home, apart from when a local bitch was in heat. Then my mother would insist that I keep him under close control.

It’s difficult to quantify the effect of the companionship I received from Rex. He followed me around persistently, reacting positively to any form of praise or stroking. How much he compensated for the lack of a father figure in my life – if at all – would take a greater mind than mine to determine. I can only state that, after my mother, Rex was a leading influence in my pre-teenage development.

There was another constant motivator from my young life, although I didn’t fully appreciate it at the time. My mother’s younger sister Winifred ('Winnie') had married a local ex-RAF man Eric. They lived in the nearby town of Elland. As my cousin Keith was less than two years younger than me, I had an instant connection on our visits. But it was Auntie Winnie and Uncle Eric who proved to be an inspiration for me.

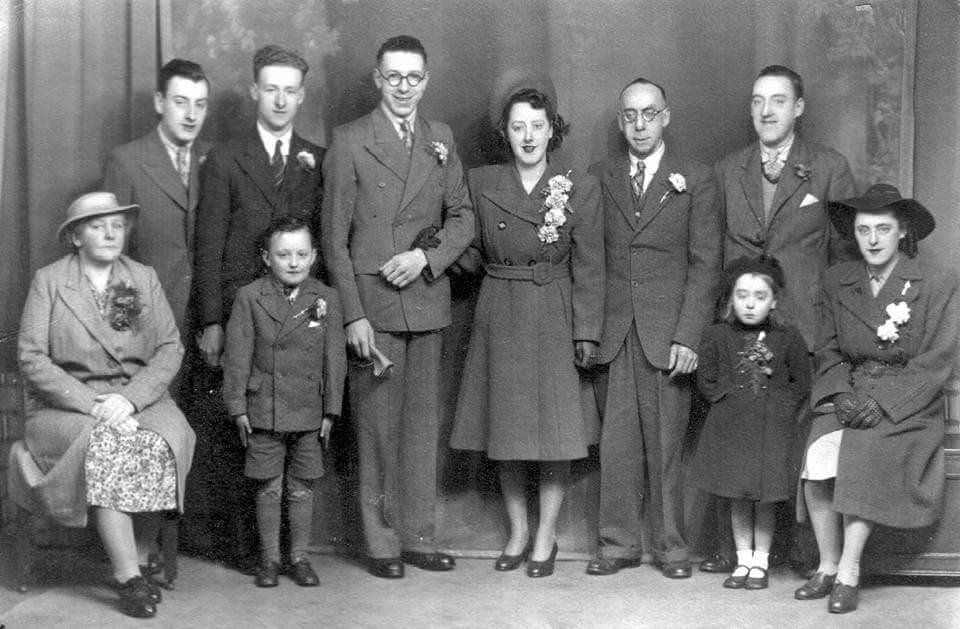

The Wedding of Eric Lightowler & Winifred Leonard March 1948

BR:

James Leonard; Best Man; Eric & Winifred, James Owen Leonard; Thomas Leonard

FR:

Mrs Dyson (Eric’s mother); Daniel Leonard; Hazel Leonard; Catherine Margaret Leonard

[Although I was alive at the time, I was not included in the photo]

Whenever I visited their home I was always impressed by the tidiness of the house – theirs had carpets where ours still had linoleum floorcoverings throughout. But the facility that really captivated me was the small workroom that amateur engineer Eric had built off his kitchen. His work tools were all stored away neatly, whilst he had a something which I had never seen before, an open-fronted display cabinet with small boxes containing his large sorted collection of screws, nails and bolts. I found these fascinating then, and still do.

Eric was a scout leader and therefore used to encouraging new skills in boys. That he was the person who taught me to ride a bicycle – using Keith’s – was no surprise. He was always willing to help where he could.

He and Winnie had an obviously happy marriage; this was to last for over 60 years. Most importantly, they accepted me without prejudice, which unfortunately was not always the case for an illegitimate child in the 1950s. I will always be grateful for their support, for demonstrating to me that there were good people around after all.

Milk, Malt Extract, Cod Liver Oil and Terrifying Dentists

One often overlooked policy of the Conservative governments in the UK during the 1950s and beyond was that of actively promoting improvements in the health of children. This initiative had been introduced by the Labour regime at the end of the war and was continued when the opposition came to power. It was felt that children needed supplements at the time to make them stronger and boost their resistance to prevalent illnesses. Paradoxically, it has since been shown that a major contributor to ill health nowadays – obesity – was much less a problem then, as wartime years of sugar rationing had produced generations of relative lightweights.

Those of my era still remember free school milk with mixed feelings. It was decreed that every child should have a bottle of milk every day at school: a 1/3 pint (190ml) measure. The bottles were delivered in crates very early in the morning and left out in the open, to be taken inside when the school staff arrived. This meant that in winter the full fat pasteurised milk could still literally be frozen at mid-morning break, the allotted serving time. Conversely, the summer contents were often well on their way to being curdled when offered up. And the supervising teachers would insist that every drop was finished. No lactose intolerance considerations then, it appears.

The provision of free school milk to junior schools was scrapped in 1971 by Margaret Thatcher, then Education Secretary, giving rise to the political and playground chant “Thatcher, Thatcher, Milk Snatcher”.

An additional children’s health insurance measure was to make extract of malt and cod liver oil available to all, again free of charge. The malt came as a glutinous brown liquid in a large brown glass bottle with a screw top lid. A tablespoon at bedtime, if I recall correctly. There were also smaller bottles of cod liver oil to be administered, this time a teaspoon daily. I quite liked the taste of the malt, so my routine was first the oil, then quickly the malt. That left a final pleasant taste in my mouth to overcome the remnants of the barely tolerable cod liver oil.

Free School Meals

Throughout the whole of my time at Deighton – like the majority of classmates – I was eligible for free school meals. It wasn’t until I moved up to secondary education that I realised that actually paying for school meals was the norm.

Every Monday morning started with the school meal register. Names were called out and those few paying would bring their packets with money up to the teacher. The rest of us just made it clear that we didn’t need to pay, although I cannot recall how we did this.

For a short period, I know that there was an experiment to provide lunches at our school also during the holidays. I recall that I went up on the first day, to find no-one around. I never went back.

I later found out that I’d turned up a day early, but the take up for the meals proved to be so poor that the trial was quickly dropped. It appears that holiday freedoms outweighed the restrictions of fixed mealtimes for most of the eligible children, although the sympathies behind this proposal were commendable.

Shopping 'On Tick'

We had everything that we wanted around Riddings Road: a local shop at the bottom of the road, with fish’n’chip and newsagent outlets just up around the corner. Even the local cinema – the Rialto – was within a five minutes’ walk. In 2020 these buildings are still recognisable there, although the cinema is now a church, the newsagents a barber’s, and the chippie has changed to a general takeaway. But the shop is still functioning, now transformed into a franchised convenience store.

At a time when most were paid their wages or allowances in cash on a Thursday, the corner shop offered one service unavailable at the other outlets: regular customers could get items 'on tick'. This meant that the shopkeeper would allow the sale of basics – bread, milk, tea, etc. – without immediate payment, to be recorded in his book for cash settlement at the end of the week. In a poor area like Deighton, this arrangement allowed his establishment to maintain continuous business. However, it did run the risk of non-payment.

I would sometimes be sent to the shop by my mother to get something 'on tick'. For security, the shopkeeper would only accept request notes from youngsters; I couldn’t simply go in and ask for something without payment. I recall that on one occasion I was told to tell my mother that “If this isn’t paid for by the end of the week, I’ll put details in the shop window”.

As instructed, I informed my mother and immediately forgot about it. He’d said this to others previously.

A couple of months later, my animated mates called for me saying “Come and look at the shop!”

When we got there, the whole window was covered with notes showing the names of people and the amounts they owed. (I remember looking – my mother’s name was not there).

As can be imagined, this caused a local outcry. Their upset was multiplied the following day when an article about the shop owner’s actions was the headline in the Huddersfield Examiner daily newspaper.

I recall loud comments being made by individuals outside the shop to the effect of “That’s the last time I shop there!”. It was so exciting for us youngsters, an entertaining diversion from our nearby game of marbles.

In the event, I don’t recall the shop getting any less busy, although a sign to the effect of “Please don’t ask for credit, as refusal can often offend”

was placed there. And I’m sure that trusted customers could still get goods 'on tick'. The owners were not going to shoot themselves in the foot.

Hardcastle Crags

At a point during my primary school years I was officially designated an underprivileged child. Or so it was described in the local newspaper report of an event to which I was then invited. Probably six or seven years old, I was part of a group taken by local taxi drivers for a charity day out at Hardcastle Crags.

We were picked up outside Huddersfield Railway Station and driven to and from the beauty spot near Hebden Bridge in the taxis. I don’t know why I was selected to join the group. My situation didn’t seem to be any different to that of many others I knew and they hadn’t been invited.

House Fire

Our neighbour, Laurie, was something of a peculiarity in the area; he was a Londoner born and bred. His dead of night Cockney cry “Gerraart! Yer ‘ars is on fire!”

is just about the only other thing I remember about him.

As Uncle Danny was not around at the time – he was probably away doing his Army National Service – I calculate that this potential tragedy happened in around 1956, when I was still under ten years old.

I remember that something woke me up late at night. I like to think that it was Rex, but this might be simply suggested memory. I immediately thought that I could smell smoke, so I went in to tell my mother, who was with Auntie Hazel in the next bedroom. She said not to worry; it was probably just fog. (This was not as implausible as it now sounds. This was in the days before the Clean Air Act. All houses had coal fires and instances of smog – fog thick with smoke – were commonplace).

It was then that Laurie started hammering on the door, yelling his warning.

What happened next is a blur. I remember that the smoke was discovered to be coming from a front-room settee, probably caused by a non-extinguished cigarette end. The settee was somehow dragged out into the front garden, where it lay for weeks before being taken away by the council waste disposal team. I don’t think that the Fire Brigade attended, but I could be wrong.

In life there are occurrences where you think “what would have happened if…?” This is one of them. Unfortunately, this was not to be the only instance of a house fire caused by a discarded cigarette that I was to endure; something similar happened in Berlin many years later.

This goes a long way to explain the pedantic routine I adopted of checking potential fire sources – especially when in a new environment like a hotel – before going to bed. I did this even after giving up smoking. Old habits die hard.

My Mum, the Bus Conductress

When I was around eight years old, with my Auntie Hazel and Uncle Danny already in full time work, my mother also decided to get a job. She must have been fed up after years of the routine of staying at home, managing the household without extra pay. Her surprising choice: she became a trolleybus conductress.

Travel by bus was the overwhelming first choice for Huddersfielders in the days when car ownership was only for the elite few. We may have been lacking many things among our dark satanic mills, but good public transport was not one of them.

I remember how proud I was to see my mum operating the bell system on the bus. (The bell buttons were located at the front, middle and back of each coach, both upstairs and downstairs, and were supposed to be operated only by the conductor/conductress). One ring meant 'STOPPING'; two rings signified 'SETTING OFF' and three rings – my favourite – denoted 'BUS FULL UP'.

The times that I travelled on her bus – invariably driven by the Irishman Tommy Kennedy – I would watch on with admiration at the way my mum carried out her tasks. This included reconnecting the shafts when they came away from the overhead wires, not an unusual occurrence. This involved taking out a long bamboo pole with a hook from its storage place on the underside of the bus, then using this to catch the loose rod and place it back onto the wire. Indeed, on some trolleybus routes around Huddersfield, this was a standard procedure to turn the vehicle around at the end of the line.

One particular about trolleybus travel that I vividly recall was the cost and colour of the single return ticket for children. This white ticket was a so-called “three ha’penny return”.

By way of explanation, this was in the days before decimalisation of our currency: there were twelve old pennies to the shilling and twenty shillings to the pound until 1971. Arithmetic will demonstrate that one and a half old pennies (= “three ha’penny”) was one eighth of a shilling. As the old shilling now is 5p, the then child return cost well under Ip when calculated in today’s values.

I state this because once I came home from school and asked my mother if I could have one and a half pennies to buy a ticket to go into town trainspotting with friends. She had to turn me down, because she didn’t have the spare money to give me. This memory alone puts our situation at that time into perspective.

"Streakers and Winneys"

Sometime around my ninth birthday – when I could be trusted to travel alone on public transport – my interest in trainspotting strengthened. When I had the money, I bought the latest issue of the Ian Allan specialist book which contained the listing of all engines in service. The idea then was to underline each train’s number as we spotted it – hence the hobby’s name – and compare our results with other watchers.

We on the Deighton estate had an advantage in this pastime; the main railway line to and from Leeds passed within a few minutes’ walk from our houses. The line ran along the valley below the fields behind Riddings Road. There was a convenient fence for looking down on passing trains from a safe distance but still near enough to speed read the numbers on the engines.

And the trains coming out of Huddersfield station could be seen within seconds of departure, as the valley view was unhindered for a mile or so in that direction. The give-away sign: the majority of train engines then were steam driven. On a clear day, their distinctive plumes of smoke could be recognised from afar.

As I grew more confident and bolder in my hobby, I would go with young friends to either the railway sheds at Holbeck, near Leeds, or to Doncaster station, where there was a convenient footbridge from which trainspotting was not only tolerated, it appeared to be encouraged. Even to this day I can recall the experience of the smell, the noise and the feeling of being enclosed in a cloud of steam and smoke as the mighty engines chugged out below us. Like a whole generation, I lost my fascination for trainspotting once the age of steam passed. Diesel trains just didn’t do it for me, I’m afraid.

There was another, now forgotten, advantage of living near the train lines. On more than one occasion we would go under the fence to the edge of the track, picking up coal to take away in a bag. These small pieces, which fell off the passing train tenders, made passable fuel for the open fires which every house had. When needs must…

I do not recall being punished for doing this, only told to be careful. My feeling at that time was that I knew exactly when all fast trains were due to pass, so there was no danger. However, this did not take into account the regular passing freight trains, but to my knowledge none of my friends were ever caught on the track. We knew to get in quickly, grab what we could, and get away smartly. This was also the routine we used when pinching apples and pears (“scrumping”) at a nearby orchard.

A Champion in the Pool

As Deighton Primary School did not have a swimming pool, we were taken by bus to Cambridge Roads Baths, just outside Huddersfield town centre, for weekly lessons. The building had two pools: one championship sized and the other a smaller, shallower version. We used the smaller pool for our lessons.

When we’d finished and got changed, we were all given a hot drink. If you hadn’t brought an Oxo cube, you received the standard unsweetened cocoa concoction. I tended to get this every time, as even Oxo cubes were outside our erstwhile shopping budget.

As a swimmer, I was OK, but others more naturally talented always seemed to be able to achieve better with less effort. It may have had something to do with my small, scrawny frame. However, I took swimming fairly seriously for a few years, in the hope that training would improve my moderate performances. I even joined the 'Junior Otters' section of the Huddersfield Otters Swimming Club, which trained at Cambridge Road Baths.

I recall turning up one evening to be informed that we juniors would be in the small pool for this session, as the normal large pool venue was occupied. I was annoyed, as usually having the bigger pool for our exclusive use was a major advantage of being a Junior Otter.

On the way to the changing rooms, I looked in over the balcony at the large pool. There was just a single swimmer going up and down a middle lane. I remember thinking how unfair this was. I asked my friends what was happening and received the answer “It’s Anita Lonsbrough”. The fact that it was the then British Empire and Commonwealth Games champion who was spoiling my fun even penetrated through to my young mind. And I forgave her.

Anita Lonsbrough – the first female winner of the BBC’s Sports Personality of the Year award – later went on to win the gold medal in the 200m breaststroke at the Rome Olympics in 1960 in a world record time. As well as receiving an MBE for her efforts, she had the dubious honour of having a block of flats in Huddersfield named after her. The 11-storey tower – built in 1961 – became infamous in later years for the antisocial behaviour of its inhabitants. No tears were shed when it was eventually demolished in 2016. By this time, however, Anita had long since moved away to live in Wolverhampton with her husband, former track cycling champion Hugh Porter.

On the subject of winning swimming performances, I too once won a race in the Cambridge Road large pool. In my first year at the Junior Otters, I was entered in the handicap breaststroke race over one length in the club’s championships. As an unknown newcomer, I was given a very generous start. Somehow, despite feeling as if I was simply treading water at the end, I managed to win.

I was then brought up to accept my prize. I recall that I was most disappointed with the award, although I don’t really know what I had expected to receive. It was a fountain pen in a box. Up to this time I had only ever written with a pencil, as ballpoints were yet to become generally available. My mother bought me a bottle of ink and the years of having ink-covered hands began.

A year later when I started at grammar school, all homework was expected to be in ink, so my unwanted prize did eventually find a purpose. However, I never did really master the art of filling the pen by dipping it in the bottle and squeezing the rubber tube. My covers of my exercise books all displayed a collection of ink bottle outlines, where I had used them as a base blotter when carrying out the refilling exercise.

The Two Wheeled Speed Freak

Although I had already demonstrated cycling ability, the cost of a bike was simply too much for our finances. So the next best thing was bought for my eighth birthday – a scooter. This had a strong metal construction, was red in colour, with a broad platform, medium size solid rubber wheels and a brake device actuated by pushing down a lever with your heel onto the back wheel. I went just about everywhere on my scooter.

Living in the Riddings Road area meant that, to get anywhere, you would have to go either uphill or downhill. There were very few flat sections in the district. The scooter was an aid when moving upwards, and a genuine speed machine when coming back down.

Despite warnings from my mother, I tended to throw all caution to the wind when out of her sight.

I had a friend from school who lived in nearby Sheepridge. His house was at the bottom of Wigan Lane, a hill road leading into the estate. He too had a scooter. We would go down the hill on our vehicles, racing to see who would be first to the bottom. As the pavement was too uneven, we would use the road. If my mother had known, she would have confiscated my scooter immediately, I’m certain.

One day returning from playing with him, boosted by the results we had been receiving on Wigan Lane, I decided to ride home down Deighton Road – a much longer and busier hill – also along the highway, not on the customary pavement. I remember the initial thrill of reaching a previously unattained speed. This was quickly followed by the terror of realising that my heel operated brake was not much more than an ornament. I jammed it continuously and, although it reduced my momentum slightly, I was only saved from serious injury by throwing myself off into a convenient grass verge. Thank goodness that there was no traffic around.

I like to think that my days of being a reckless driver ended there and then. The memory of the potential accident has moderated my behaviour on the road ever since.

Hawthorn Blossom, Swallows and Swifts

The area across from the bottom of Riddings Road consisted of open fields, divided by a single farm track, lined with hawthorn trees, through to the Bradley housing estate around a mile away.

I was told that this countryside would never be built on, as some of the grassland was planted on top of a previous dump for ammunitions chemicals manufactured at a nearby plant during the world wars. Indeed, in the mid-fifties there was a massive chemical fire at the far end of the fields, adjacent to the main Leeds Road. I still recall its huge black cloud and the fact that news of the fire even made the national papers. Apparently, it was started accidently by local youngsters playing with fire in a tin can.

Nevertheless, this didn’t stop the majority of this green belt area being built over with a vast new estate in the 1960s. Prior to this, however, the fields had been a haven of peace for locals, especially for us children.

It is said that smells evoke the strongest reminiscences. In my case, it is the smell of the white hawthorn blossoms along that farm track that still finds a reaction in me. Wherever I might encounter it, this special springtime aroma from my childhood immediately brings back pleasing memories.

My other strong recollection of the fields was based not on the ground, but in the air. Every summer would see the arrival of migrating flocks of swallows and swifts. Although never a birdwatcher, I did however learn to differentiate between these two types of swooping birds.

The greatest pleasure we youngsters experienced on fine summer evenings was to lie on our backs on the grass, observing the magnificent aerial display of these birds as they chased and fed on insect swarms. Regrettably, for a variety of reasons, the numbers of swallows and swifts visiting locally has since decreased substantially. At least I had this opportunity to observe them in their prime, for which I’m forever grateful.

And then we were three

In March 1957 my life structure was changed completely with the birth of my sister Carole. I was no longer an only child; I now had a younger sibling for company.

Her birthday is 5 March, whilst mine is 4 September. This makes Carole exactly nine and a half years younger than me, a fact which I have always found intriguing.

I don’t recall anything special about my mother’s period of pregnancy. Certainly, she had finished working on the buses, but Carole’s birth was nonetheless something of a surprise for me. My Auntie Hazel came to find me outside with the shouted instruction “Come and meet your baby sister!”

I remember seeing her for the first time upstairs in bed with my mother – Carole was born at home – and then asking something like “Can I go out to play now?” It’s not that I was upset by this major event in my life. I simply didn’t know how I was supposed to react.

Of course, I soon became used to sharing my mother. I was never jealous of Carole; I loved having her around and watching her grow. Carole enjoys telling the story about the time, a few years later, when I was asked to look after her whilst our mother was away. I was given money to buy something for us both to eat. With this I treated Carole to my favourite – a large jam swiss roll – to share. She’s never let me forget this cruelty!

It’s interesting in retrospect that we moved out of Riddings Road a year after Carole’s birth. I surmise that the fact my mother had given birth to her second 'illegitimate' child (Carole similarly was never told the name of her biological father) must have had some influence on this decision.

The disapproval of single mothers was still prevalent then. Neighbours were duplicitous, saying one thing to your face and the other behind your back. For this reason, my mother probably thought that, by moving away, she could escape such censure. Many of these neighbours had known her for the greater part of her life and therefore were very familiar with her personal history.

Or perhaps the house was simply too big – or expensive – for our reduced family size. Auntie Hazel and Uncle Danny were now living elsewhere.

Irrespective of the reasons, in 1958 my mother, Carole and I (accompanied, of course, by Rex) moved to 99 South Street in Huddersfield to start a new chapter in our lives.

____________________