After all that had happened in the previous decade, it was surprisingly easy to slot back into life in hometown Huddersfield. Certainly, I had matured from that naïve youth who had ventured off to military pastures new in 1966, returning home a more confident and worldly-wise grownup. But I was still a Yorkshireman at heart, comfortable in familiar surroundings, only now additionally responsible for two rapidly growing schoolchildren.

In retrospect, care of Suzanne and Paul was the least of my worries. They were adored, and thoroughly spoiled, by their cherished ‘Granny’. I never had to be concerned about asking my mum to take care of them. Indeed, she encouraged me to go out and lead my own life, saying to the kids “You’ll be all right with me, won’t you?”, receiving their immediate agreement. I think now that this was when mum was at her happiest, caring fulltime for the grandchildren she had previously only seen occasionally. Even to this day, Suzanne raves about ‘Granny’s homemade steak pie’.

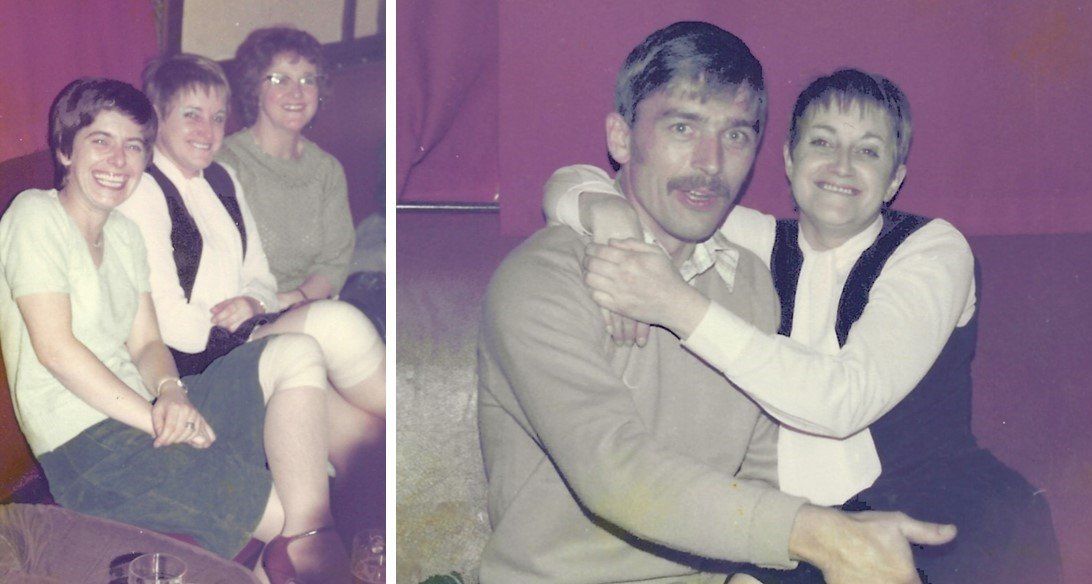

Suzanne & Paul with beloved Granny plus Norman Brook and his sister Emily at 74 Ainley Road in 1980. I too was happy. I didn’t have any immediate money problems, as I still had a couple of thousand pounds in the bank from my stint in Saudi Arabia.