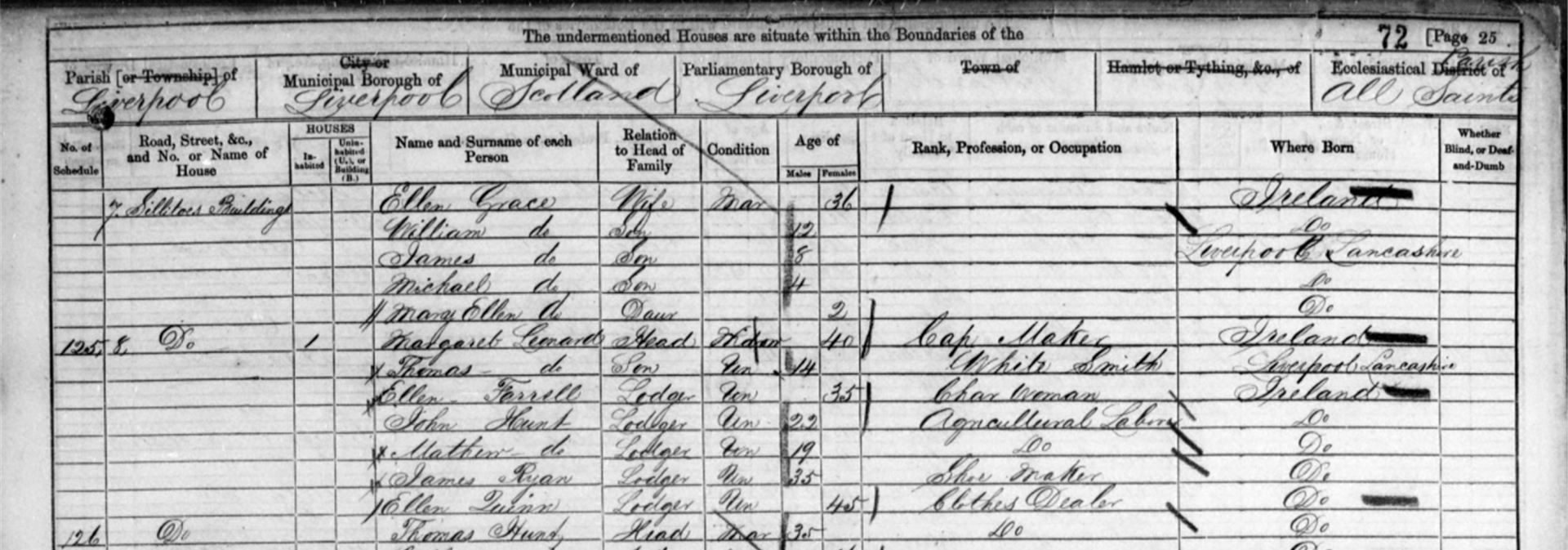

Both census records show an entry for a Thomas Leonard in Liverpool. Extract 1 shows a Thomas born around 1860, recorded with the name version “Lenard”, whilst Extract 2 shows a different Thomas born around 1847. My first reaction – encouraged by the knowledge that I had spotted it, even though the surname had a different spelling – was that the 1871 Census version was correct. (As it was probable that they were illiterate at the time, the alternative spelling of the surname is not unusual. They would probably have depended upon the judgement of the census recorder to copy out his version of what he heard).

I knew for certain that my grandfather was born in 1893. In my opinion, it was more likely that his father would be aged in his thirties (i.e. the Thomas born in 1860) rather than in his late forties (i.e. the Thomas born in 1847) at the time of my grandfather’s birth. I just needed further evidence to confirm my findings. I found this in the form of a baptism record for the Thomas born in 1860:

Note here that the Latin name given for his father is Gulielmus = William (for the pedantic reader, the above form is in the Genitive Case, translating as “of William”, giving the Gulielmi spelling of the word). This version of the father’s name was to be crucial in future research.

Having made this connection, I then progressed quickly into research of the Thomas Leonard born in 1860 in Liverpool. From the details given in the 1871 Census it could be seen that his parents – William & Mary (née Ryan) – were born in Ireland. In Clonmel, County Tipperary to be precise. I then eagerly followed their path using various English and Irish genealogy research sites.

I was so convinced of the validity of my findings that, in 2012, we took a family holiday break to Clonmel. A homecoming, so to speak. Our group – consisting of me, my wife, my sister, her partner and their teenage son – had a memorable visit, discovering interesting information about this branch of the Leonard family, due in no small way to the great assistance of a researcher at the Tipperary records collection at Thurles Library. Alas, for all our efforts, this chosen path was incorrect. It would have been a heritage to be proud of. But it wasn’t ours.

END OF EXPLANATION OF INCORRECT INITIAL CONCLUSION

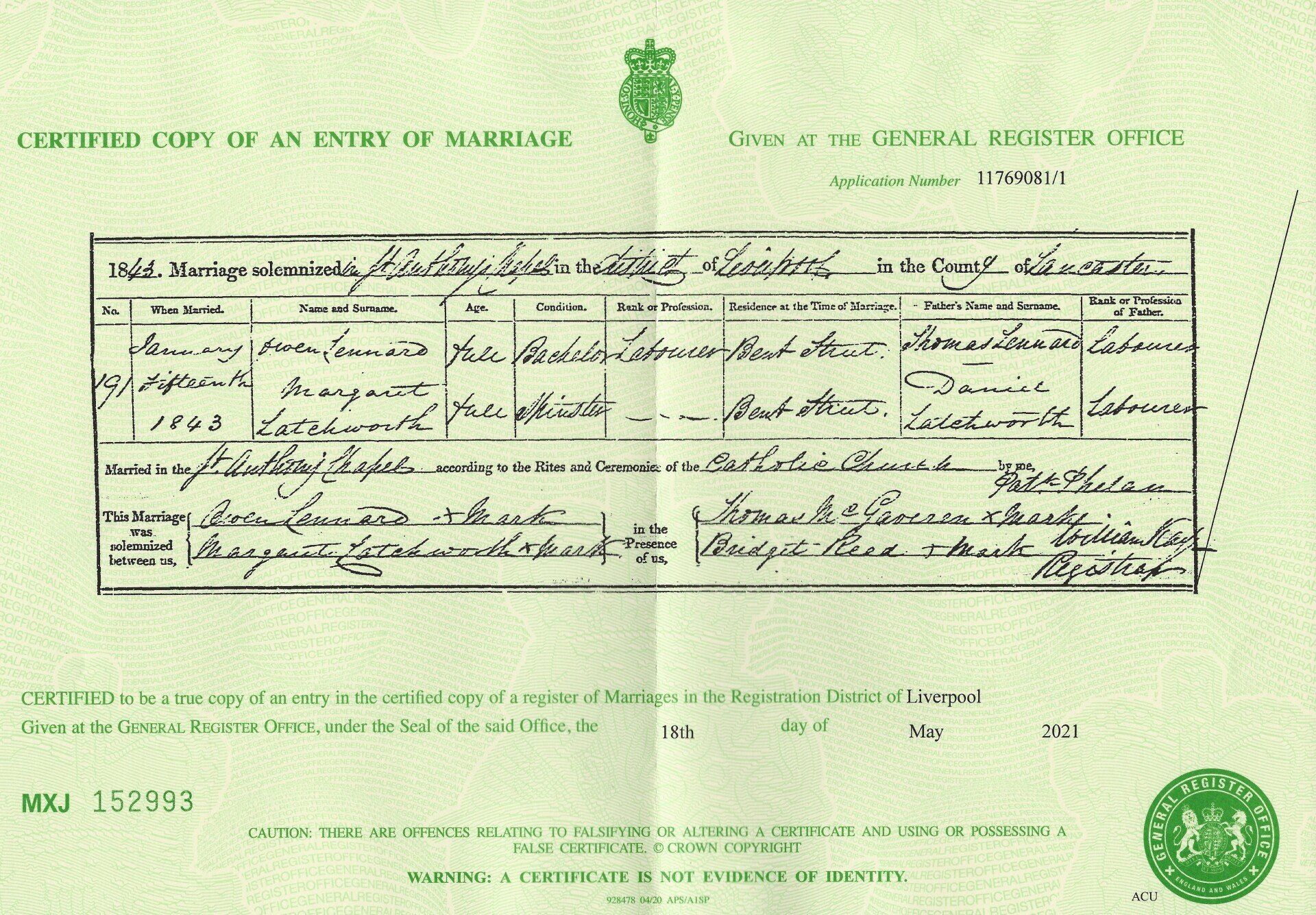

Jumping forward to late March 2021, I received a copy of the marriage certificate for Thomas Leonard and Catherine O’Malley from my cousin’s daughter Caroline Lightowler who lives in Canada. She had ordered it from the General Registry Office. A copy is shown below: